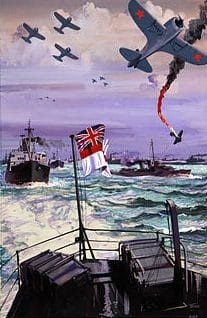

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, demanded help and Britain and its allies provided supplies. The most direct route was by sea, around northern Norway to the Soviet ports of Murmansk and Archangel. The first convoy sailed in September 1941.

The convoys were coded depending on their route – initially PQ for outbound, QP for homebound. From 1943, the codes changed to JW and RA – outbound and homebound respectively.

There were 78 convoys between August 1941 and May 1945, with two gaps with no sailings between July and September 1942, and March and November 1943. About 1,400 merchant ships delivered essential supplies to the Soviet Union under the Lend-Lease program, escorted by ships of the Royal Navy, Royal Canadian Navy, and the U.S. Navy.

Conditions were among the worst faced by any Allied sailors. As well as the Germans, they faced extreme cold, gales and pack ice. The loss rate for ships was higher than any other Allied convoy route.

Their route passed through a narrow funnel between the Arctic ice pack and German bases in Norway, and was very dangerous, especially in winter when the ice came further south.

Many of the convoys were attacked by German submarines, aircraft and warships. Convoy PQ17 was famously and very sadly almost entirely destroyed.

When Convoy PQ-17, sailed from Iceland on 27 June 1942, headed for the Soviet port of Arkhangel, they faced stiffening German air and naval defences, brutal Arctic temperatures, and around-the-clock daylight, which meant no protection from the cover of darkness. The Arctic route known as “The Murmansk Run” was about to turn deadly for the men and ships of PQ-17.

Initially, PQ-17 had a strong escort and covering force, including the battleship USS Washington to protect the 35-ship convoy from attack. Two ships were forced to turn back enroute, leaving 33 merchantmen to face the gauntlet of German attacks which began on 2 July 1942.

Attacks against the convoy steadily increased until 4 July when the Admiralty got word that the Tirpitz, the sister ship to the German battleship Bismarck, was sailing to intercept the convoy. Not wanting to risk the destruction of the warships, the Admiralty sent the following messages to the convoy commanders, late on the evening of 4 July:

2111 Hours: Most Immediate. Cruiser force withdraw westward at high speed.

2123 Hours: Immediate. Owing to the threat of surface warships, convoy is to disperse and proceed to Russian ports.

2136 Hours: Most Immediate. My 2123 of the 4th. Convoy is to scatter.

These words sent chills down the spines of the men sailing in these merchant ships. Whilst the thought was that scattering the convoy would make it harder for the Germans to sink the ships, what followed was the exact opposite and spelt disaster for PQ-17.

Without support from warships and left to fend for themselves, the merchant ships were sitting ducks for the German Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe and many men and ships involved with PQ-17 would not survive. On 5 July alone, 12 merchant ships were sunk by German attacks.

Out of a total of 35 ships in the convoy, only 11 reached Arkhangel. Matériel losses in the convoy were staggering: 3,350 vehicles, 210 aircraft, 430 tanks, and 99,316 tons of other cargo such as food and ammunition were lost. Adding insult to injury, the reports of the Tirpitz coming out to intercept the convoy were false.

Winston Churchill called PQ-17 “one of the most melancholy naval episodes in the whole of the war.” The heavy losses of PQ-17 and the follow-up PQ-18 in September, caused convoys to the Soviet Union to be suspended until December 1942.

During this episode of the war and in total, 85 merchant vessels and 16 Royal Navy warships (two cruisers, six destroyers, eight other escort ships) were lost. Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine lost a number of vessels too, including one battleship, 3 destroyers, 30 U-boats, and many aircraft.

Despite these terrible losses, over four million tons of supplies were still delivered to the Russians. As well as tanks and aircraft, these included less sensational but still vital items like trucks, tractors, telephone wire, railway engines and boots.

Although the supplies were valuable, the most important contribution made by the Arctic convoys was political. They proved that the Allies were committed to helping the Soviet Union, whilst deflecting Stalin’s demands for a ‘Second Front’ (Allied invasion of Western Europe) until they were ready. The convoys also tied up a large part of Germany’s dwindling naval and air forces.

The Artic Convoys was undoubtedly a gruelling campaign like many others during the second world war, although it wasn’t until December 2012 that this was officially recognised with the establishment of the “Arctic Star”, a campaign award for which all British and Commonwealth service personnel who took part became automatically eligible. Sadly for many, that was too late but they will be ever remembered.

Our thanks to IWM for some of the detailed statistics above.