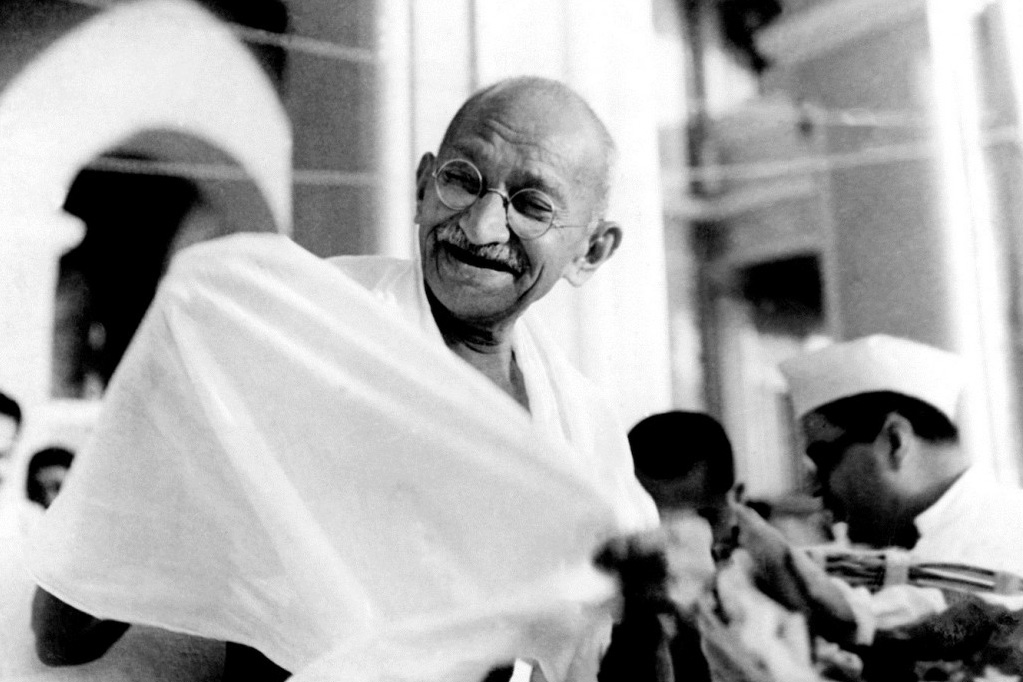

The decade of the 1940s stands as a monumental chapter in India’s long and arduous struggle for independence, a period defined by the escalating fervour for self-rule against the backdrop of a world consumed by war. At the epicentre of this transformative era stood Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the Mahatma, a figure whose moral authority and unwavering commitment to non-violent resistance shaped the destiny of a nation and left an indelible mark on the global landscape of political and social change. His leadership during this critical decade, marked by both triumphs and profound disappointments, showcased the potent yet complex application of Satyagraha in the face of imperial power and burgeoning internal divisions.

The Shadow of War and the Intensified Demand for Self-Rule

As the Second World War cast its long shadow across the globe, the British Empire, deeply embroiled in a fight for its very survival, found its attention and resources diverted from its vast colonial holdings. Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, recognising this shifting global dynamic, perceived an opportune moment to intensify their long-standing demand for complete independence, or Purna Swaraj. Gandhi, a staunch critic of fascism and all forms of oppression, initially offered a nuanced stance, suggesting conditional support for the British war effort. This support, however, was contingent upon a clear and unequivocal commitment from the British government to grant India complete independence once the war concluded. You can learn more about the Indian National Congress at its historical overview on Wikipedia’s page about the Indian National Congress.

Gandhi’s perspective was rooted in a deep moral conviction. He believed that India, a nation aspiring to freedom and self-determination, could not morally align itself with a power that denied it the very same rights. His conditional offer aimed to leverage Britain’s wartime vulnerabilities to advance India’s cause, hoping that the exigencies of the global conflict would compel the imperial power to reconsider its hold on the subcontinent. However, this nuanced position also sparked debate within the Congress, with some leaders advocating for unconditional support for the Allied cause while others favoured a more assertive stance demanding immediate independence regardless of the war’s outcome.

The Cripps Mission Debacle and the Birth of the Quit India Movement

The year 1942 proved to be a pivotal turning point, marked by the arrival and subsequent failure of the Cripps Mission. The British government, under mounting pressure both domestically and internationally, dispatched Sir Stafford Cripps with proposals for a future Indian constitution. However, the offer of Dominion status – a form of self-governance within the British Commonwealth – after the cessation of hostilities fell far short of the Congress’s unwavering demand for immediate and complete independence. Further details on the Cripps Mission can be found at this page on the UK Parliament website.

For Gandhi and the Congress leadership, the Cripps proposals were not only inadequate but also deeply disappointing, perceived as a tactic to placate Indian nationalist sentiments without any genuine intention of relinquishing power in the near future. The failure of these negotiations shattered any lingering hopes of a negotiated settlement based on gradual progress towards self-rule.

In response to this perceived betrayal and the deepening frustration among the Indian populace, Gandhi, with the full backing of the Congress, launched the historic Quit India Movement on August 8, 1942, during the Bombay session of the All-India Congress Committee. His powerful and unambiguous call to “Do or Die” resonated like a thunderclap across the nation, galvanising millions of Indians to actively participate in a non-violent struggle to end British rule. The movement demanded an immediate withdrawal of the British from India and urged every Indian to become their own liberator through non-cooperation and civil disobedience. More information about the Quit India Movement is available on this historical site.

The Iron Fist of Repression and the Eruption of Spontaneous Resistance

The British government’s reaction to the Quit India Movement was swift, brutal, and uncompromising. Viewing the movement as a direct threat to their wartime efforts and their imperial authority, they unleashed a wave of repression unparalleled in its scale. Within hours of Gandhi’s impassioned speech, he, along with virtually the entire top echelon of the Congress leadership, including Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, were arrested and incarcerated without trial. Accounts of these arrests and the government’s response can be found in various historical records, including those detailed on the National Archives of India website.

This preemptive strike aimed to decapitate the movement and extinguish its momentum. However, the absence of centralised leadership, rather than crippling the movement, inadvertently led to a surge of spontaneous and localised resistance across the length and breadth of India. Ordinary citizens, students, peasants, and workers, inspired by Gandhi’s call and fuelled by years of pent-up frustration, took to the streets in defiance of British authority.

The forms of resistance were varied and widespread. Strikes paralysed industries and essential services, protests and demonstrations filled public spaces, and acts of civil disobedience, such as the refusal to pay taxes and the defiance of prohibitory orders, became commonplace. In some regions, driven by intense anger and the lack of clear guidance from their arrested leaders, some participants resorted to acts of sabotage, disrupting railway lines, damaging government property, and engaging in confrontations with the police and military. While Gandhi had consistently advocated for a purely non-violent struggle, these instances of violence, though localised, deeply troubled him and stood in stark contrast to the principles he espoused.

Imprisonment, Profound Loss, and the Moral Force of the Fast

Imprisoned in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune, Gandhi endured a period of immense personal suffering and loss. During his confinement, he witnessed the tragic deaths of two of his closest companions: his beloved wife, Kasturbai Gandhi, who had been his steadfast partner and fellow traveller in the struggle for decades, and his devoted secretary, Mahadev Desai, whose intellectual and emotional support had been invaluable. These personal losses inflicted a deep emotional wound on Gandhi, yet his spirit and his commitment to the cause of independence and non-violence remained unyielding. Biographies of Mahatma Gandhi, such as Richard Attenborough’s “Gandhi” (film), often depict this period of profound personal loss.

In February 1943, while still held captive, Gandhi embarked on a significant 21-day fast. This act of self-suffering was a powerful moral protest against the British government’s accusations that the Congress and Gandhi himself were responsible for the violence that had erupted in the wake of the Quit India arrests. Gandhi argued that the government’s heavy-handed repression had incited the violence and that the Congress had consistently called for non-violent resistance. Accounts of Gandhi’s fasts and their political impact can be found in historical analyses of the Indian independence movement.

Gandhi’s fast garnered widespread national and international attention, drawing sympathy for the Indian cause and putting immense moral pressure on the British regime. The prospect of the Mahatma, a globally revered figure, dying in prison due to a self-imposed fast sent shockwaves across the world and further delegitimised British rule in the eyes of many. The government, facing mounting pressure, eventually allowed Gandhi to complete his fast, but his health had been significantly weakened.

The Unwavering Tenets of Satyagraha

Throughout the tumultuous decade of the 1940s, Gandhi’s philosophy of Satyagraha, often translated as “truth force” or “soul force,” remained the unshakeable foundation of his political action. He believed that by adhering to truth and non-violence, individuals could appeal to the conscience of their oppressors and ultimately achieve justice. Satyagraha was not merely a passive resistance; it was an active and courageous engagement with injustice, employing methods of non-cooperation, civil disobedience, and self-suffering. You can explore the principles of Satyagraha further on resources like the GandhiServe Foundation website.

Gandhi’s commitment to ahimsa (non-injury or non-violence) was central to his philosophy. He believed in the inherent sanctity of all life and advocated for the avoidance of violence in thought, word, and deed. He argued that violence only bred more violence and that true and lasting change could only be achieved through peaceful means.

Equally important was the principle of self-suffering. Gandhi believed that by willingly enduring hardship and pain without retaliation, Satyagrahis could purify themselves and touch the hearts of their adversaries, exposing the injustice of their actions. His own fasts were powerful examples of this principle in action.

Navigating the Shifting Political Landscape and the Path to Negotiation

Following his release from prison on medical grounds in May 1944, Gandhi, though physically weakened, remained a potent force in the Indian political landscape. The end of the Second World War brought about a significant shift in the global order. A weakened British Empire, burdened by the costs of war and facing growing international pressure for decolonisation, began to reconsider its long-term presence in India. The impact of World War II on the British Empire is a well-documented historical phenomenon.

Gandhi, recognising this changing context, engaged in a series of crucial negotiations with the British government, now represented by a Labour administration more sympathetic to the cause of Indian independence. He also held discussions with the Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, in an attempt to find a mutually acceptable solution that would preserve the unity of India while addressing the concerns of the Muslim minority. Information on the Muslim League’s perspective can be found on historical archives and academic resources.

However, the deep-seated communal tensions between Hindus and Muslims, exacerbated by years of political manoeuvring and differing visions for the future of the subcontinent, proved to be a formidable obstacle. The Muslim League’s demand for a separate Muslim state, Pakistan, gained increasing traction, fuelled by fears of marginalisation in a Hindu-majority India.

The Agony of Partition and the Futile Plea for Unity

Despite Gandhi’s tireless efforts to bridge the chasm between the Congress and the Muslim League and to foster Hindu-Muslim unity, the political climate continued to deteriorate. The British government, increasingly convinced that a unified India was no longer a viable option, began to formulate plans for the partition of the subcontinent. The Mountbatten Plan, which outlined the partition, is a key historical document of this period.

For Gandhi, the prospect of partition was a profound personal tragedy and a stark contradiction to his lifelong advocacy for a secular and united India. He vehemently opposed the division of the nation along religious lines, believing that it would unleash widespread violence and sow the seeds of long-term conflict. He engaged in intense discussions and appeals, urging both Hindu and Muslim leaders to reconsider their positions and find a way to coexist peacefully within a single nation. Accounts of Gandhi’s opposition to partition are widely available in historical texts and biographies.

However, the momentum for partition had become seemingly unstoppable. The escalating communal violence in various parts of the country, coupled with the political deadlock between the Congress and the Muslim League, ultimately led to the British government’s decision to proceed with the division of India.

The Final Stand for Peace Amidst the Flames of Communal Strife

The partition of India in August 1947 was accompanied by horrific levels of communal violence, as millions of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs were displaced and subjected to brutal atrocities. This period of bloodshed and chaos was a devastating blow to Gandhi’s lifelong commitment to non-violence and communal harmony. The scale and brutality of the partition violence are documented in numerous historical accounts and survivor testimonies.

In the face of this widespread carnage, the ageing Mahatma, despite his deep disappointment and anguish, embarked on courageous peace missions to the violence-torn regions. He travelled to Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Delhi, putting his own life at risk to appeal for sanity, compassion, and an end to the bloodshed. His presence and his powerful message of peace had a remarkable calming effect in many areas, offering a beacon of hope amidst the darkness of communal hatred.

His fast in Calcutta in September 1947, undertaken to protest the Hindu-Muslim violence in the city, was a powerful demonstration of his moral authority and his willingness to sacrifice himself for the cause of peace. Similarly, his final fast in Delhi in January 1948, just weeks before his assassination, was a desperate plea for communal harmony and for the newly independent India to uphold its secular ideals. Details of Gandhi’s peace missions and fasts during the partition period can be found in historical analyses of the era.

The Enduring Legacy of a Non-Violent Revolution

Tragically, Mahatma Gandhi’s life was cut short on January 30, 1948, when he was assassinated by a Hindu extremist who opposed his efforts for Hindu-Muslim unity and his secular vision for India. His death was a profound loss for the nation and the world, silencing a powerful voice for peace and non-violence. Information about Gandhi’s assassination and its context is widely available in historical records and academic studies.

However, despite the tragic circumstances of his passing and the pain of partition, Gandhi’s unwavering commitment to non-violent resistance throughout the 1940s and the preceding decades played an instrumental role in achieving India’s independence. His philosophy of Satyagraha demonstrated the potent power of moral force against the might of an empire, inspiring millions to participate in a peaceful revolution that ultimately led to the liberation of a nation.

Gandhi’s legacy extends far beyond the borders of India. His principles of non-violent resistance have inspired countless movements for social justice and political change across the globe, from the American Civil Rights Movement led by Martin Luther King Jr. (further information available at The King Center website) to the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. His life and teachings continue to serve as a powerful reminder of the transformative potential of non-violence in the pursuit of a more just and peaceful world. The tumultuous 1940s, marked by both the triumph of independence and the tragedy of partition, stand as a testament to the enduring power and the complex challenges of Mahatma Gandhi’s unique and transformative approach to political action.